Return to Nepal

Written on 8th July, 2022I’ve got some unfinished business in Nepal. My last garden at Chelsea (in September 2021), for which I was awarded a Gold Medal, was originally slated for May 2020, but Covid put paid to that. One of the saddest and most frustrating things about being forced to reschedule was having to completely redo the plant list, and miss out on a huge range of wonderful and exciting plants that flower in early summer, and ever since I said goodbye to the primulas, cardiocrinums, arisaemas and rhododendons, I have been longing to see them growing in their natural habitat.

So, one air ticket and a sleepless overnight flight to Kathmandu later, I find myself bumping through the clouds, approaching Lukla airport on a short internal flight, to being my trek in the Himalayan foothills, hoping to unearth some of those treasures.

The Himalayas are a rich hunting ground for flowering plants that can survive in the UK, a fact not lost on early plant hunters such as Joseph Hooker, Victorian explorer, botanist, cartographer and close confidante of Charles Darwin, who, from 1847 to 1851, travelled much of the region, collecting about 7,000 plant species including many previously unknown kinds of rhododendron, meconopsis and primula. Most of the temperate flowering plants occur here between 2-4000m above sea level, and with such a wide range in altitude, I’m excited by what lies ahead.

I’m met by my PG, my guide and fixer, and Saila, my porter, who will happily carry my rucksack, like the unfit, over equipped westerner than I am. It’s the done thing here, and so I quickly reconcile myself to this luxury. We’re taking the route to Everest Base Camp, at least part of the way, and will be making detours off that route, up lesser known valleys and hidden gorges to get off the beaten track a bit.

Things start very well, and despite the long journey so far, I’m thrilled to start spotting plants I know. The scenery is stunning. We pass through pretty villages, unchanged for decades, except perhaps the odd satellite dish and corrugated iron roof, replacing slate tiles. At elevations of around 3000m it takes a day or two to acclimatise, and it’s still quite warm. On the climb I come across arisaemas in full flower. A. tortusosum are the pick of the bunch, with their long green or purple erect tail like central spadix rising whip like out of the spathe. Arisaemas are found in forests and forest edges, and even open slopes and flower in early summer. I make a mental note to plant more of them at home, and for adventurous clients.

The sumptuously bright yellow euphorbia wallichii have a long season of interest and are at their peak, and the thalictrums are just starting to show, especially thalictrum virgatum. Like most species plants, it’s a small thalictrum and I find them growing almost horizontally out of the side of a steep, rocky bank, sprays of little white flowers showing up against the dark wet rocks behind. There are two species of instantly recognisable polygonatums: polygonatum verticilatum, and the seemingly less cultivated but arguably more interesting polygonatum cirrhifolium. Both form a slender column to more than 50cm tall of primly erect stems, clothed at intervals with whorls of very narrow pointed leaves, and I see them flowering, in, respectively, clusters of small cream, and pink flowers hanging along the upper ends.

Further along the trail, I round a corner after climbing some steep steps, and am greeted by the sight of two roses in full flower, against a backdrop of pines and sorbus. Rosa sericea and rosa macrophylla form large, rangy plants, towering over us, putting on a show. I will see r. sericea on quite a few occasions over the next few days but the r. macrophylla here is so glorious that even the trekkers have stopped for a breather, and to take a look. We’re at about 3300m on a fairly open, south facing slope, approaching Namche Bazar, and it has dark purple stems with solitary bright pink flowers. Glorious.

Higher than Namche, at 3700m and up to 4500m, the plants start to change, and we enter the habitat of the primulas, finished lower down but still flowering up here. It’s cooler here, and we spend days walking in the cloud. Three primulas stand out for me: the diminutive primula rotundifolia, with rounded toothed leaves, and purple flowers with a yellow eye, found only in caves and under overhanging rocks, leading me to assume that it doesn’t like direct rain, or excessive moisture; primula denticulata with their mauvish blue flowers in compact globular heads, standing out against a carpet of fallen pine needles, enjoying some shade; and sulphur yellow primula sikkimensis, enjoying a more open aspect, in a wet meadow, fertilised by copious quantities of yak dung.

I’m also thrilled to come across a few solitary but instantly recognisable fritillaria cirrhosa with green flowers and, when I peer underneath, brown spots inside.

The meconopsis however, elude me for most of the trip. One day, Saila finds a solitary plant, tucked in next to a rock at the bottom of a scree slope, protected from the wind, with a bit of shade from an overhanging rose. We spend far too much time tracking them down and, this find aside, only manage to come across m. paniculata, nearly in flower, at about 4500m on a south facing scree slope by the side of a stream, standing two feet high with fat, but closed, flower buds , rather than the two metres that they can attain, with their incongruously yellow (rather than blue) flowers. In spite of this disappointment, I feel like we’ve strayed gloriously off the beaten track, and am rewarded with glimpses of towering snow capped peaks, as the clouds swirl around us.

Rhododendrons are almost over, but aside from the dwarf species which are still in full flower, the ubiquitous r.arboreum of varying shades of red and pink, and r. camplyocarpum, with yellow, almost transluscent flowers offer a tantalising glimpse of what the valleys must look like earlier in the season.

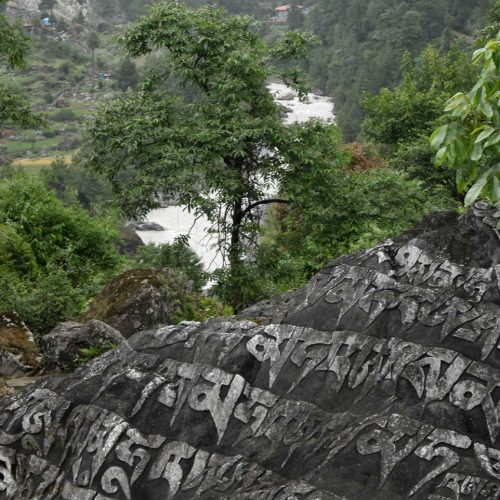

We walk from guest house to guest house, living simply but comfortably enough, changing valleys, aspect and altitude every day, absorbing the culture as much as the plant life, and the scenery never fails to excite me, especially when crossing huge gorges via swaying suspension bridges, torrents of water raging far below, or when walking through charming villages, past intricately carved mani walls and boulders, or through forest of trees festooned with frayed prayer flags, fluttering in the breeze.

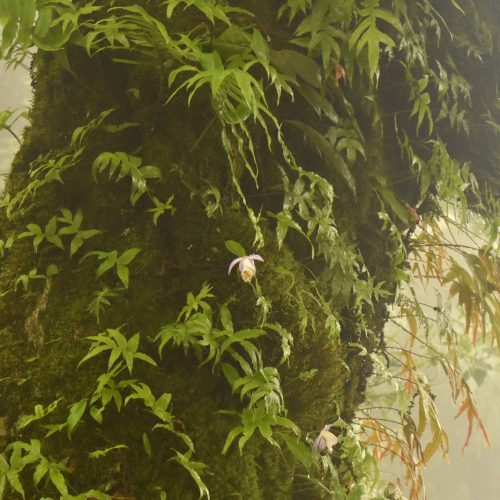

Eventually we drop to around 2000m, having been forced to walk out to the nearest road as the cloud cover has closed Lukla airport for the foreseeable future, and I have a flight to catch from Kathmandu that won’t wait for me. I’m rewarded with a whole new range of plants, more suited to the warmer, almost sub tropical conditions. Tiny, jewel like pleione hookeriana, smaller than crocuses, epiphytes actually, drawing all their nutrients from the air and water, stud large moss covered rocks in the middle of streams, and on the shady side of large trees.

Cardiocrinum giganteum, for me the most impressive plant of the original Chelsea plant list, greet me as I round one corner, reaching more than two metres into the sky, everything about them oversized; thick glossy stems with dinner plate sized fleshy leaves, and white trumpet shaped flowers the size of, well trumpets.

Scheffleras as big as small trees, unmistakable with their neat, evenly palmate leaves at the end of sturdy erect stems, stand out against the surrounding mess of jungle, and rodgersia nepalensis are in full flower, creamy inflorescenses high above pleasingly crinkled textured leaves, growing as high as my waist. Roscoea purpurea are also at their peak, in pleasingly large colonies on the steep banks. I took a few roscoeas as a souvenir from my Chelsea garden when the show ended, and planted them in my own garden in London, in the shade of camellia japonica, and among some ferns, and I make a mental note to water them heavily when I get back, to ensure a long and flowering season with a generous display, in late summer.

Finally, we reach the road, and a rather less fun bone jarring 15 hour jeep trip awaits us, on the return to Kathmandu.

As usual, I’ve only really scratched the surface of what is on offer here but I don’t have a diary as empty as Joseph Hooker’s. Botanising is a tricky pastime, especially if your time is short. You have to go with the flow and make the most of what you find when you come to a certain country.

Here in Nepal, Come in March and the magnolias and michelias will be glorious but it will be on the chilly side and most things will have barely started growing; April and May for rhododendrons and primulas, but the guest houses will be full of trekkers and you’ll have to queue for everything (worth it though); June for ariseameas, cardiodrinums, euphorbias, roses and philadelphus (but don’t forget to pick your valley, and altitude, carefully – and this applies at all times of the year) and from July onwards you will see aconitums, selinums, ligularias, thalictrums, lilium nepalese and possibly, if you are very lucky, the bloody meconopsis!